Over the past few months, I’ve been testing out the beta version of iOS 11 on my iPhone, and I’ve found myself doing something very disturbing – I regularly tell Siri little fibs, and sometimes I tell her full blow lies.

The “Do Not Disturb While Driving” Feature

iOS 11 was released yesterday, and one of its most important new features is called “Do Not Disturb While Driving.” If you enable it and set it to “Automatic,” your iPhone will detect when you’re moving fast enough to be driving which will trigger two main things.

First, it stops displaying all Notifications such as tweets, texts, and weather alerts. Second, when someone calls or texts you, it sends an auto-reply saying that you’re driving and that you’ll respond to them later.

Based on statistics showing an increase in accidents caused by distracted drivers and laws in 47 states banning texting while driving (my home state of Texas finally passed one this month), there is some hope that this will prevent more needless fatalities.

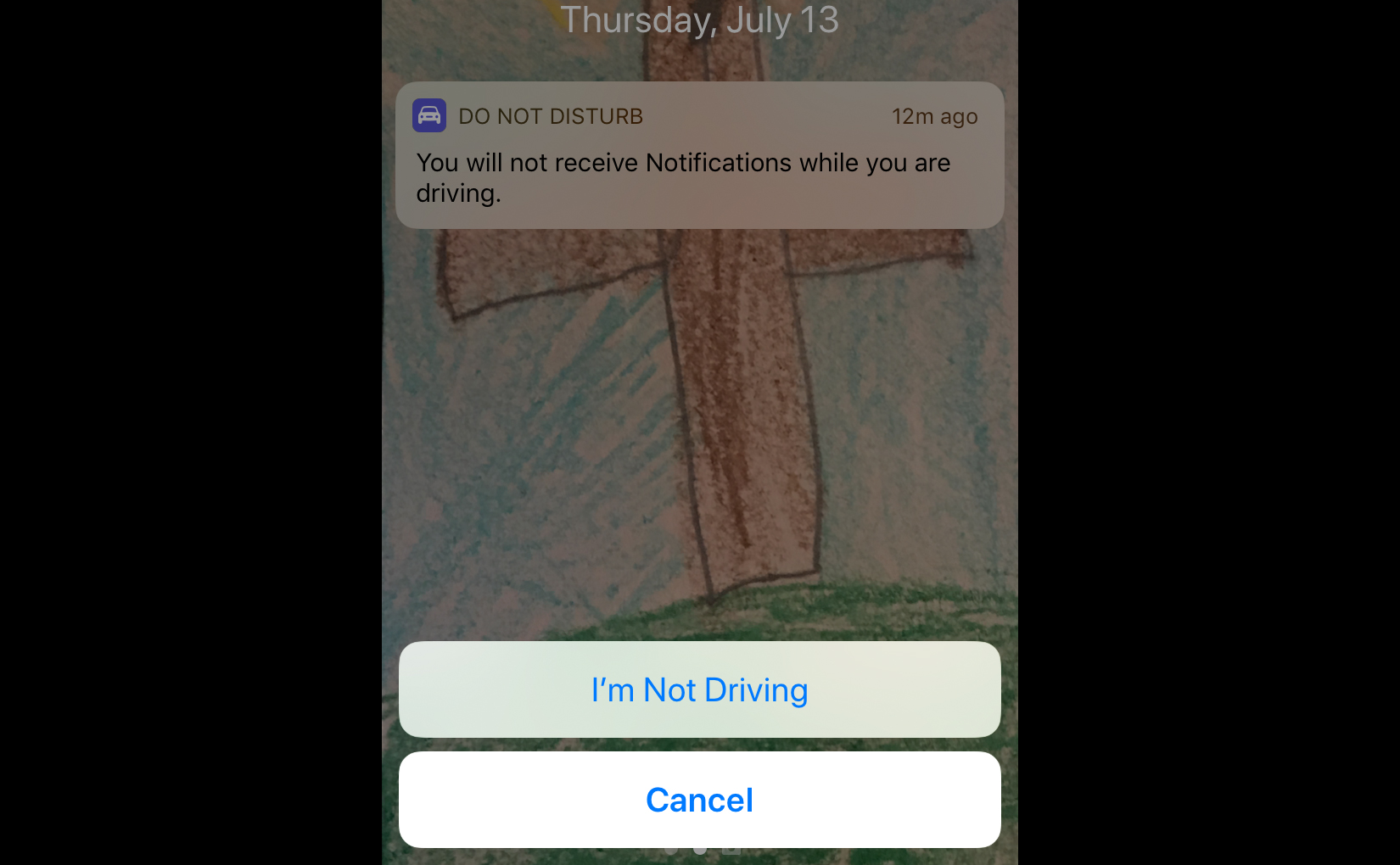

But I think the more interesting aspect of this feature is what happens when you attempt to use your phone while driving. If you click the home button, a dialog comes up that says “Do Not Disturb While Driving is Enabled,” and it presents the user with two buttons: “Cancel” and “I’m Not Driving.”

A White Lie That Grew and Grew

Notice that the second button doesn’t say “Disable” or something machine-oriented. Instead, Apple has chosen to make the button into a statement that you, the user, say about yourself. In doing so, Apple isn’t letting you to just turn off the feature without telling your device something that is either true or false.

During the Beta period of iOS 11, I had a chance to test this while I sat in the passenger seat as my wife drove for part of road trip. When I took out my phone, I truthfully tapped “I’m Not Driving” and caught up on some emails.

But then a little later, I found myself at a stop light, needing to get directions.

I tried voice commands, but when “Do Not Disturb While Driving” is enabled, the screen won’t show you any feedback. This makes using Maps very challenging. (Other features, such as voice texting, are also visually downgraded while driving).

Desperate for directions, I gave in and pressed the “I’m Not Driving” button, reasoning that while I was in the driver’s seat with the car in gear, I wasn’t actually moving and the light was still red. After tapping the button, I quickly setup directions before the light turned green, and all was well. No big deal.

But soon after that first little fib, I inevitably found myself driving and simultaneously feeling that I “legitimately” needed a phone function that I couldn’t get to via voice commands. In retrospect, I could have pulled over, but it was just this once, and I’m special, right?

So, while I was driving, I tapped “I’m Not Driving.”

And in doing so, I lied to a $700 object made of plastic, glass, and rare metals.

Conditioned to Lie

I’d like to think that the “Do Not Call While Driving” feature will at least cause drivers to think about how much they use their phones in the car. But my prediction is that in the next few weeks, millions of people will begin doing the exact same thing that I, to my shame, did. It’ll start small with a “legitimate” purpose, but eventually it’ll snowball and people will just tap “I’m Not Driving” as unthinkingly as we all check the “I’ve Read the Terms and Conditions” box.

Unfortunately, this will come quite naturally to us, not because we’re liars, but because of the way computer user interfaces (UI) are designed. Over the past few decades of computer use, we’ve been presented with thousands of buttons that say “OK” and checkboxes that say “I’ve read …” This has taught us that interacting with computers and devices means tapping whatever button is in the way of what we want.

This probably wasn’t terribly significant when the stakes were low, and it might seem hyperbolic to call it “lying.” But when we bend the truth about reading the Terms and Conditions, there aren’t kids in the roads or oncoming vans full of people.

Now that people’s lives are at stake, I worry that this “habituation of the button” will essentially render Apple’s well-intentioned new feature powerless. If someone wants to get new directions while sitting in traffic – or much worse, check their likes while cruising a residential street – they just have too many years of practice clicking through whatever is in their way to stop now.

Technology vs. Bad Habits

While I don’t think “Do Not Disturb While Driving” will ultimately work, I do think that this feature signals more what’s coming with technology and with ourselves. At least as far back as monks who created accurate clocks to prompt their times of prayer, humans have attempted to use technology to prompt good behavior and prevent bad behavior.

In recent years, a variety of tracking apps and have been built with the belief that if technology can just show us how few steps we take in a day, that we’ll be motivated to live healthier lives.

And it seems that when a person is already motivated to change, these tools can really work. I’ve personally become a much better runner since using RunKeeper. But when a person doesn’t want to change, we’ve also seen that they’ll do whatever it takes to find a way around the technology. There are plenty of people who sit on their couches shaking their Fitbit up and down while binge-watching Netflix shows just to ensure they get lower insurance premiums.

Advanced Technology Will Require Advanced Deceit

Shaking a FitBit or tapping a button might not seem like soul-forming activities, but in the coming years our devices will only grow smarter and our interactions with them will become more humanlike. This means that the methods we will use to skirt the system will similarly become more humanlike.

In other words, as technology get better at tracking us or warning us about bad behavior, we’ll have to get better at lying and deception in order to get around it. Like an alcoholic chiseling off his ankle monitor, we will click, tap, break, or lie to whatever sits in the way of what we want. One day, we might need to look an android in the camera and tell it something untrue, just like we do to other humans.

In this sense, technology will continue to do what it always does – reflect back to us what’s happening deep within us. Like a mirror, our interactions with technology have the potential to show us not what we say we value, but what we truly desire when we think no one is looking. Remember, technology, like God, is always watching.

Shaping Our Souls

You might think it’s hyperbolic to say that tapping “I’m Not Driving” while driving is lying. After all, it’s just an inert device and a few hundred million lines of code. But the truth is that none of our actions, however private they seem to us, happen in a vacuum.

Tapping that button not only endangers others around us, it also forms our souls in a particularly destructive way. When I choose to act in untruthful ways, even with a machine, I’m developing a pattern and a practice in my life. I am inculcating myself in a world of alternative facts where truth is defined by what I want rather than what truly is.

So when you update to iOS 11 and you find that “I’m Not Driving” button looking back at you, spend just a second thinking about what the interaction is telling you about yourself and the orderliness of your desires.

And then, for the sake of both your neighbor’s body and your own soul, put your eyes back on the road.

Thank you for yet another thought provoking post.

I would love to hear more about how you (or you suggest we) respond to those terms and conditions radio buttons. Extreme cases make things interesting 😉

A couple of thoughts: 1) Reinke argues that no-texting laws actually make things worse: phones lower, therefore eyes on road less. Amazing that we try to legislate morality and it has an opposite effect. I wonder what the effect will be of people trying to disable something so that they can continue to be non-focused. For Christians this is a love-your-neighbor issue. But we’re selfish, and my ability to send or receive immediate information is more important than the other person on the highway. It’s really that simple.

2) “Unfortunately, this will come quite naturally to us, not because we’re liars, but because of the way computer user interfaces (UI) are designed” I think it comes quite naturally to us because, in fact, we are liars and have grown accustomed to justifying our lies. UI may help us along in our justification, but it’s not the root.