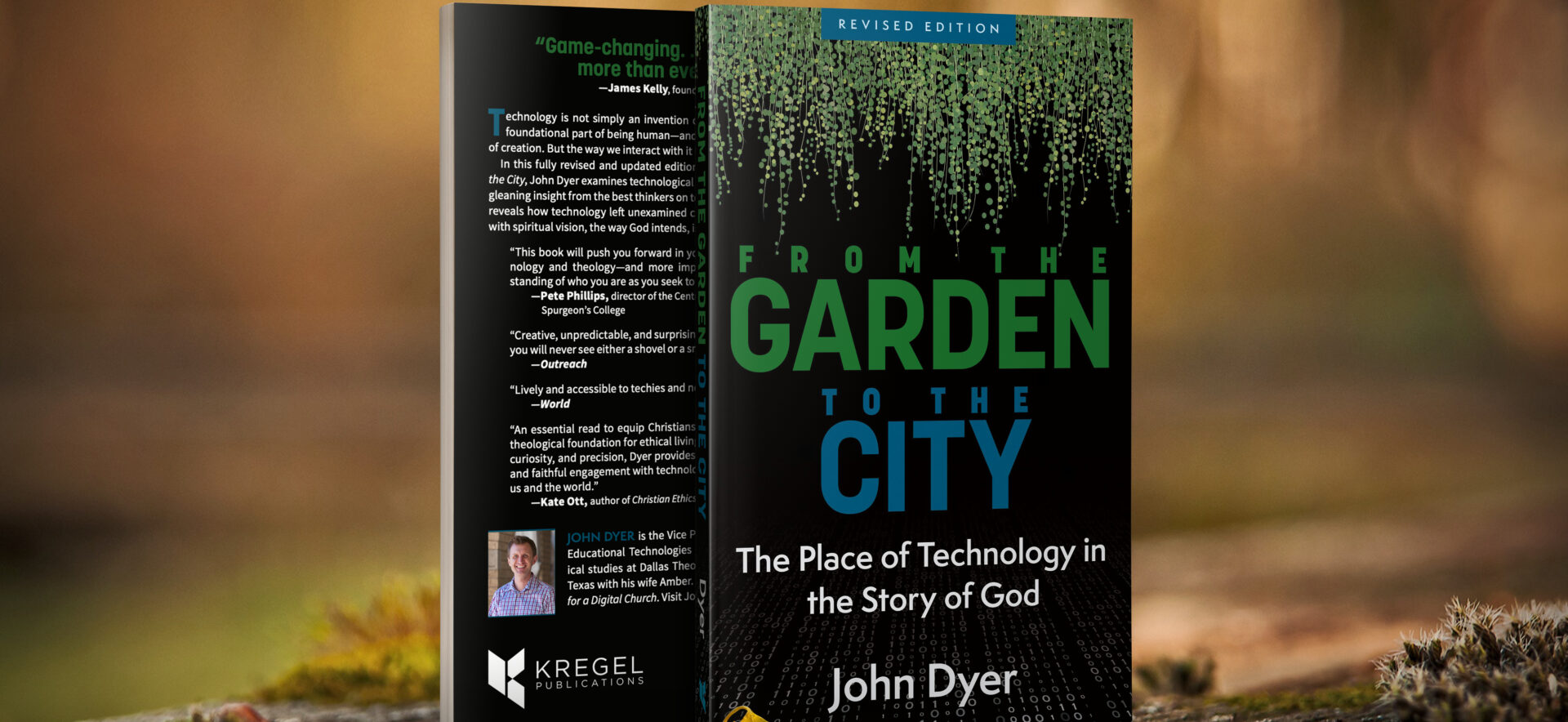

Today is the official release day of From the Garden to the City revised edition!

The book has has a new cover, a new subtitle (formerly The Redeeming and Corrupting Power of Technology and now The Place of Technology in the Story of God), and about 14,000 more words (Microsoft Word says there were 4,221 changes!).

I have joked that all it took was replacing “MySpace” with “TikTok” and “MP3” with “Spotify” but the actual changes are much more substantial than that. Here are a few things that are new or updated:

- Some examples of technological change were updated. For example, the shift from records to tapes to CDs to MP3s needed an update to include streaming services like Spotify.

- Although it is not an academic book with heavy scholarly interaction, some updated references were added to reflect more of current discussions about technology, faith, and ethics.

- Some smaller sections within chapters were expanded with some new ideas. In the chapter on Creation, I added a section considering what the first 3 of separation and second 3 days of filling in Genesis 1 might tell us about our own processes of making.

- Post-pandemic, online church (and the reason I don’t think we should call it “disembodied”) get a much more extensive treatment than in the original when only a few of us had tried it.

- Sections on AI, transhumanism, virtual reality, metaverse, and cryptocurrency were either expanded or added. These are not in depth discussions, but should offer some initial framing for classes or discussion groups.

- The final chapter includes an extended discussion on 10 ways that ancient tools differ from modern devices. The book argues that, going back to the Garden, technology is and has always been a God-given good. But today’s smartphones and shovels do have some categorical differences and this sections explores this.

- 3-4 questions were added at the end of each chapter for personal or group discussion.

- There’s also now an audiobook version!

Here is the text from the Preface to the Second Edition:

One of the perils of writing about technology is that it becomes dated before the ink dries. the file saves. syncs to the cloud.

In the decade since the first edition of this book was published, our world has continued to accelerate technologically, with once futuristic technology becoming mainstream (cryptocurrency, virtual reality, smart speakers, self-driving electric cars) and mainstream technology becoming commonplace (phones, social media, videoconferencing). Even with all this change, the core argument of the book—that theologically, technology is a good gift from God that plays a significant part in the biblical story; and that practically, technology is never neutral but has an embedded value system that transforms individuals and communities—is still true. And yet these technological accelerations and cultural movements invite updated examples and new reflection.

In the category of technology that has become commonplace, perhaps the most life-altering has been the way phones have come to saturate our lives. In 2010, we still called them “smartphones,” and they were only just transitioning from the toys of the tech elite into the ubiquitous, ever-present, always-on glowing rectangles that permeate our lives. Our phones make incredible things possible, both good and bad, but they are significant not just because of what we can do with them but because of how we have rearranged our lives around them. We wake up to their alarms, respond to their notifications, record our most (in)significant moments with their cameras, and then scroll through their feeds as we fall asleep. Phones not only have reshaped our individual habits but they have also made larger societal shifts possible, such as enabling developing countries to skip wired phone and internet connections altogether, empowering “remix culture” where individuals collect and arrange values and beliefs to their tastes, and empowering companies like Uber to transform the transportation industry and Spotify to disrupt the music industry.

The ubiquity of phones, in turn, accelerated the use of social media, which was just emerging from college culture (Facebook) and Silicon Valley (Twitter) in the early 2010s. New platforms have come and gone (remember Google+?), and different demographic groups gravitate toward some platforms more than others, but social media is now a part of everything from schools and churches to politics and medicine. As with phones, the list of good and bad uses of social media is endless, but underlying that are profound changes to society, including political elections that centered on the use and abuse of social media, the rise of misinformation campaigns that accelerated an erosion of trust in traditional societal structures, and heightened tensions around important issues of justice and human rights.

The pandemic of 2020 and the lockdowns into 2021 only accelerated these technological changes, and people around the world embraced and adapted to digital technology literally overnight. The idea of online church was a mere footnote in the first edition of this book, but by mid-2020 it was something nearly every religious person in the world had experienced along with online school, remote work, and grocery delivery. It is difficult to imagine how things would have played out if the pandemic had taken place twenty years before, when the internet was still young and tools like livestreaming and videoconferencing were not yet widely available. But today it is difficult to imagine life, relationships, and business without them.

As we experienced these accelerations of mainstream technology becoming commonplace, we have also become more aware of the technology which was just coming on the market in 2010. For example, Bitcoin was invented in 2009, but it took years for it and its crypto-competitors to make their way into mainstream financial discussions. Virtual reality (VR), too, has been around for decades but has recently gone from being an expensive experimental technology to something that costs less than a phone to try and is now the focus of many companies, like Facebook’s parent company, Meta. Talk of robots and artificial intelligence (AI) has also entered the mainstream, where AI can be loosely defined as anything we used to think only humans could do. This includes deepfake videos, self-driving cars, and medical diagnoses, and will expand to more in the years to come. As we talk to our smart speakers, ideas about the singularity, transhumanism, bioethics, and designer babies have also emerged from science fiction into podcast discussion points and everyday conversations.

Each of these events and trends are worthy of deep engagement and thoughtful discussion, though I can’t fully address them all in an update to this book. But I have attempted to bring the examples and references throughout this edition into conversation with these events, while continuing to argue both that technology is still a good part of our image-bearing creativity and that, more than ever, we need godly wisdom developed in community to faithfully navigate this new world. I hope these updates will allow us to faithfully and soberly embrace technology as one of God’s many good gifts.

I hope you enjoy the new edition! If you pick one up, I’d love it if you’d leave a review on Amazon.

And keep an eye out for another release next month: People of the Screen: How Evangelicals Created the Digital Bible and How It Shapes Their Reading of Scripture!