Image: Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, Bathsheba, and Mary by Sally Poet

The Question

Sometimes a friend’s tweet can send you down the internet rabbit hole in the best way possible. This is one of those times.

A few weeks ago, my friend Amy Peterson (please read her fantastic books) asked a question on Twitter about whether there are any scenes in the Bible which meet the Bechdel-Wallace test. Amy offered a preliminary answer and so did some other friends, including Jessica Hooten Wilson. This intrigued me and made me want to fire up a code editor to look into the question more deeply.

The Test

In case you’re not familiar with it, the Bechdel-Wallace test “is a measure of the representation of women” in movies and books. It is based on a comic by Alison Bechdel that suggests a work must contain a scene with (1) at least two women, (2) who talk to each other, (3) about something other than a man. Though it wasn’t in the original comic, many also agree that both characters must have names.

The films in the Star Wars can serve as an example of the test’s usefulness. The first Star Wars movie was praised for presenting a strong female character in Princess Leia. However, the only other named character in the movie is Aunt Beru, but she and Leia never meet or talk, so the film fails the Bechdel test. In contrast, The Force Awakens (episode VII) includes a scene in which Rey and Maz Kanata discuss Rey’s destiny and the Force, which passes all three elements of the Bechdel test (see below for some disputes about this).

It has been pointed out that the Bechdel test has its limitations—a bad piece of art can can pass it (some argue that the Sir Mix-a-Lot song “Baby Got Back” could pass) and a good film could fail it (Gravity has a female protagonist but very few characters)—but it remains a helpful shorthand for evaluating representation and bias.

The Discussion

Around the web, the question about whether the Bible passes Bechdel has been considered before in Reddit threads and in posts on specific areas like the story of Ruth or Jesus’ interaction with women. But the clearest overall answer comes from an Anglican priest in Melborne who blogs under the name Paidiske, the Greek word for “female slave or servant.”

Paidiske summarizes the narrative books that pass and fail the Bechdel test, and then she groups the books that fail into several categories: those where no women speak, those where the women who speak are not named, and those where named women either speak only about men or only to men. Her taxonomy can be visualized by further breaking the elements of Bechdel test into five categories:

| Books | Named | Woman | Speaks | To a Woman | Not RE:Man |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ruth, Mark, Luke | • | • | • | • | • |

| Genesis, John | • | • | • | • | |

| Exodus, Samuel, Kings | • | • | • | • | |

| Numbers, Joshua, Judges, Chronicles, Esther, Daniel, Acts | • | • | • | • | |

| Job, Jeremiah, Matthew | • | • | • | ||

| Leviticus, Deuteronomy*, Ezra, Nehemiah, Isaiah*, Ezekiel, Hosea*, Amos*, Jonah, Haggai, Zechariah*, Revelation | ? | ? |

Note: Paidiske does not consider books that are not narrative (e.g., Proverbs and Ephesians) and notes that *Deuteronomy, Isaiah, Hosea, Amos, and Zechariah are mixed genre and not entirely narrative.

The Data

Although the question has been asked and answered before, Amy’s tweet and Paidiske’s post made me wonder if I could do a data-driven analysis that would might help me find things I would have missed on my own.

Thankfully, Robert Rouse of viz.bible has produced an incredible open source dataset of people, places, and events throughout Bible, linking together passages of scripture in a rich way. For example, he has identified six different characters named “Mary” and ten named “Joseph,” marking all the verses where they appear, even if the text uses a pronoun like “she” or “him.”

This allows us to look for verses where people who meet certain criteria are mentioned near one another. For example, we could search for passage where members of the Trinity appear together or, in our case, where women have a conversation.

The Analysis

People in the Bible

Before getting to the specifics of the Bechdel criteria, I ran some numbers to get an overview of the people in Robert’s dataset. It currently has 3070 characters, including the members of the Trinity, angels, demons, some unnamed people, and so on. Although it’s still a work in progress and needs more contributors, it is a wonderful and powerful resource he has created for free.

The table below summarizes the number of characters currently in the dataset, their sex, and when they appear alongside another character of the same or opposite sex within one verse.

| Total | Linked to Men | Linked to Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Persons | 3070 | — | — |

| Men | 2866 | 2487 | 540 |

| Women | 202 | 191 | 94 |

Obviously, this shows us that there are far fewer women than men in the Bible. In addition, we can see that only about half of the female characters appear alongside other women, while men appear next to men much more often. Although is not a comparison project, it is worth noting that the Quran has one named woman (Mary) and other religious texts like the Bhagavad Gita have none.

People Interacting in the Bible: Bechdel #1

To find verses that meet the first Bechdel criterion (two women in a scene), I used the people dataset to find verses where more than one female character appeared either in the same verse or in an adjacent one.

This brings up the first of several cases where there is some nuance to the data that requires a manual decision. For example, sometimes the name of a person appears in a passage that is not actually a scene where the person is present, acting, or speaking. Genesis has several examples of this, such as passage where two women are mentioned but do not act or speak (Gen 4:19), the mention of “daughters” (Gen 5:4), or names of people in genealogies (Gen 5:9). I did a bit of manual filtering to include primarily scenes of action or dialogue.

| Books | Chapters | Verses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 66 | 1189 | 31102 |

| Narrative Books* | 33 | 838 | 24056 |

| Mentioning a Man | 66 | 972 | 10707 |

| Mentioning Two+ Men | 58 | 705 | 7149 |

| Mentioning a Woman | 41 | 217 | 783 |

| Mentioning Two+ Women | 19 | 70 | 221 |

| Verified Scenes with Two+ Women | 19 | 68 | 217 |

This data indicates that there are 68 chapters where two women appear together and therefore have the potential to meet the first criterion of the Bechdel test.

Conversations in the Bible: Bechdel #2

For the next Bechdel criterion, instead of starting with the list of scenes from above and narrowing in, I looked for any passage where a woman speaks, so that the data would include all the scenes in Paidiske’s taxonomy, including when women speak to men, crowds, or supernatural beings.

In my first attempt, I used the the viz.bible data to find tagged female characters near a conversation. This only found 225 verses, so I ran additional checks for pronouns (“she”) and titles (“daughter”, “woman”) which brought the number up to 769 verses, and then manually limited that down to when a woman was the speaker.

| Books | Chapters | Verses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tagged with Men in Conversations | 50 | 664 | 3168 |

| Tagged with Women in Conversations | 22 | 78 | 225 |

| Manually Verified Women Speakers | 23 | 94 | 261 |

Again, there is some fuzziness to this because some scenes include actual words of dialogue while others only report that one person speaks to another without including the words. For example, Esther chapter 2 only includes one line of dialogue (Est 2:2-4), but also several instances where the author tells us that characters are speaking to each other (Est 2:10, 15, 18, 20, 22). Below, I’ll point out some instances of women speaking in the epistles that surprised me.

Conversation Topics: Bechdel #3

The next task was to look at the conversations themselves and determine whether or not they meet the third Bechdel criterion of discussing something other than a “man.” This is designed to filter out scenes where female characters are reduced to discussing a love interest, a hero, or a villain, but some scenes are harder to classify.

In the example above from Star Wars episode VII, during Rey and Maz’s conversation, they talk about the Force, but they also mention men (Luke and Vader) and one of the objects they discuss is related to a man (Luke’s lightsaber). Some have objected that this means the conversation doesn’t truly pass the spirit of the Bechdel test.

In the Bible, this question comes up most often when women discuss pregnancies, usually of male babies, or when they discuss things that are related to a man. In addition, when a women converses with a non-gendered being (e.g., God or Satan), it isn’t as clear how to classify the conversation.

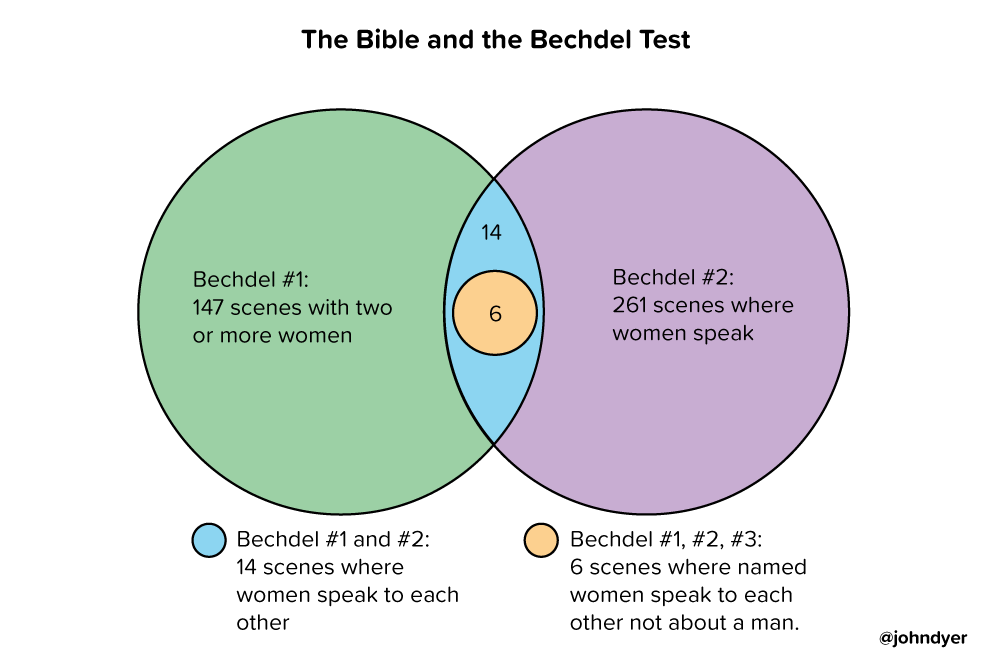

The following table and Venn diagram attempt to summarize these findings. Please download the entire dataset, let me know if I’ve missed anything, and make your own calls on each scene.

| Books | Chapters | Verses | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scenes with Two+ Women | 19 | 68 | 217 |

| Scenes with a Woman Speaking | 23 | 94 | 261 |

| Overlap: Women Speaking to Women | 7 | 14 | 14 |

| Named Women Speaking to Women not about a Man | 3 | 4 | 6 |

The Results

So does the Bible pass the Bechdel test?

This short answer is: yes, there are scenes where two named women have a conversation not about a man.

The longer answer is more complex, but also, I think, richer.

Although there are comparatively few female characters in the Bible and few scenes that unambiguously pass the Bechdel test, rereading the scenes where women appear shows that, as helpful as the Bechdel test is, it doesn’t tell the full story. Where men are gallivanting all over the pages of scripture, during the key movements of the story when God is making major moves toward saving the world, faithful women are always present and prominent. It’s almost as if in world of patriarchy and misogyny, the presence of women function as markers that say, “Pay attention, this is important!” for each major movement of the biblical story.

Part of my interest in this is because I like playing with Bible data, but the deeper reason is that I am married to an incredible woman whose depths I have only just begun to see over the last 15 years, and I am father to an indescribably interesting young woman who asks deep and challenging questions, including many about the place and value of women in the world. While much of the discussion above is technical and categorical, my heart is exploring how the fullness of God’s image can be valued in all creation and the biblical story.

The Story

In the second half of this post, I’m going to retell the biblical story using the Bechdel analysis as guideposts.

The Beginning

Genesis begins by ensuring that readers know that all humans—”male and female”—are created in God’s image (Gen 1:27). Then, in Genesis 3, Eve speaks to the serpent (Gen 3:2) and to God (Gen 3:13) on equal footing with Adam (see below for a discussion of this scene in 1 Timothy). Although these scenes don’t pass the Bechdel test, my friend and colleague Sandra Glahn suggests a new test is needed where, “a named woman having a conversation with a being that outranks a man about something other than a man gets extra points in the representation scale.”

As we read on, we find that the rest of Genesis can be a brutal place, especially for women, who are often exploited, sexualized, and mistreated by men or one another. There are several scenes where women directly address one another (meeting Bechdel #1 and #2), but these usually have to do with men. Lot’s (unnamed) daughters, for example, only speak when discussing a plan to sleep with their father (Gen 19:31-32). Similarly, Rachel and Leah’s only recorded conversation concerns aphrodisiacs and who will sleep with their polygamist husband Jacob (Gen 30:15). Rachel’s unnamed midwife speaks to her about her delivery (Gen 35:17), but then she dies and Jacob renames their newborn son.

Genesis also contains the launch of God’s plan to redeem humanity through a single human family, and in that story comes a powerful scene derives some of its significance precisely because it doesn’t meet the Bechdel test. In Genesis 12, God promises that he will make the decedents of Abram and his wife Sarai (both named in Genesis 11:29) into a great nation (Gr. ethnos) through whom he will bless all people groups. Sadly, Abram and Sarai fail to trust that God can give them a child, and in the process, they abuse Sarai’s servant Hagar. Sarai and Hagar’s dialogue is not recorded, but if it were, it would likely not pass the Bechdel test and be quite nasty.

However, the words of Hagar that are recorded make her the first character in scripture to give God a name.

She gave this name to the Lord who spoke to her: “You are the God who sees me,” for she said, “I have now seen the One who sees me.”

Genesis 16:13

This is one of the first instances where not passing the Bechdel test is what gives the scene its power. In the midst of pain and suffering, God sees our suffering and is working to redeem it.

The Exodus

In one of the next great movements in the scriptures, God rescues Abraham and Sarah’s decedents from captivity in Egypt. Although Moses becomes the one of the central figures of our faith, his origin and life are marked by women, including a key story that includes a literary device that intentionally fails the Bechdel test.

Exodus 2:1-8 tells the story of Moses’s birth, rescue, and naming. Initially, none of the characters are named; they are simply referred to by titles like “a man of the tribe of Levi,” “a Levite woman,” “a baby boy,” “his sister,” and “Pharaoh’s daughter.” Later, his mother and sister are named (Jochebed in Exodus 6:20; Miriam in Ex 15:20), but Pharaoh and his daughter are consistently referred to by their titles.

In a key scene, two women discuss what to do with the child. This scene very nearly passes the Bechdel test, but because the princess is not named, it doesn’t fully qualify. However, the scene ends with Pharaoh’s daughter naming the baby based on her own agency, indicating that this entire passage is constructed to draw a contrast in perceived power and weakness, and to show how God saves:

Then his sister asked Pharaoh’s daughter, “Shall I go and get one of the Hebrew women to nurse the baby for you?” “Yes, go,” she answered. So the girl went and got the baby’s mother. Pharaoh’s daughter said to her, “Take this baby and nurse him for me, and I will pay you.” So the woman took the baby and nursed him. When the child grew older, she took him to Pharaoh’s daughter and he became her son. She named him Moses, saying, “I drew him out of the water.”

Exodus 1:7-9

And let us not forget that Moses was saved a second time by another (named, speaking) woman (Exod 4:24-26)!

The Negotiators, Leaders, and Prophetesses

As we continue through the biblical story, we encounter passages in Paidiske’s taxonomy that fail the Bechdel test because they only pass the third criterion, with named women speaking not about men, but to men or crowds rather than other women. Jessica Hooten Wilson mentioned two key instances including the women in Numbers 27 (cf. Joshua 17) and Deborah’s song in Judges 5.

The daughters of Zelophehad son of Hepher, the son of Gilead, the son of Makir, the son of Manasseh, belonged to the clans of Manasseh son of Joseph. The names of the daughters were Mahlah, Noah, Hoglah, Milkah and Tirzah. They came forward and stood before Moses, Eleazar the priest, the leaders and the whole assembly at the entrance to the tent of meeting and said, “Our father died in the wilderness. He was not among Korah’s followers, who banded together against the Lord, but he died for his own sin and left no sons. Why should our father’s name disappear from his clan because he had no son? Give us property among our father’s relatives.”

So Moses brought their case before the Lord, and the Lord said to him, “What Zelophehad’s daughters are saying is right. You must certainly give them property as an inheritance among their father’s relatives and give their father’s inheritance to them.”

Numbers 27:1-7 (cf. Joshua 17:3-6)

Judges 4 and 5 include the actions and words of Jael and Deborah, and although the two characters never meet or speak, they are significant in terms of representing women more than 3000 years ago as whole persons, capable certainly of being wives and mothers, but also leaders, negotiators, prophets, and stone cold assassins.

On that day Deborah and Barak son of Abinoam sang this song:

Hear this, you kings! Listen, you rulers!

I, even I, will sing to the Lord;

I will praise the Lord, the God of Israel, in song. …In the days of Shamgar son of Anath,

Judges 5:1, 3, 6

in the days of Jael, the highways were abandoned;

travelers took to winding paths.

The Blessing is Passed (along with the Bechdel Test)

The next major movement of the Biblical story is usually understood through the establishment of the Davidic Covenant and the promise of a righteous king whose just reign would be eternal. It is interesting then, that this event is preceded by and dependent upon the clearest case of the Bible passing all three elements of the Bechdel test.

In the opening chapter of Ruth, Naomi, Orpah, and Ruth discuss men—their dead husbands, the prospect future marriage, and Boaz—but they also talk to one another about their lives, their relationship to each other, and their work (Ruth 2:2). In the middle of these conversations comes one of the most beautiful passages in all of Scripture, one that fulfills the promise of God’s chosen people bringing the good news to all nations told through a conversation between two widows, both foreigners and immigrants:

But Ruth replied, “Don’t urge me to leave you or to turn back from you. Where you go I will go, and where you stay I will stay. Your people will be my people and your God my God. Where you die I will die, and there I will be buried. May the Lord deal with me, be it ever so severely, if even death separates you and me.” When Naomi realized that Ruth was determined to go with her, she stopped urging her.

Ruth 1:17-18

The Scriptures Are Found!

The highpoint of Ruth stands out even more sandwiched between the brutality of Judges and the books of Samuel, Kings, and Chronicles. In these books, women are rarely recorded speaking to one another (1 Sam 25:18-19), but women do speak, and one scene just before Israel and Judah’s final demise stands out to me as major movement.

In 2 Kings 22, we meet King Josiah, who ascends to the throne at age 8. Eighteen years later, he decides to clean up the temple, and in the process, one of the priests famously recovers “the scroll of the law” (2 Kgs 22:8). After being broken by hearing the words of scripture for the first time, Josiah doesn’t consult the priests, but instead asks five male priests to seek the wisdom of Huldah the prophetess.

This seems to be another instance in which not passing the Bechdel test heightens its significance:

So Hilkiah the priest, Ahikam, Achbor, Shaphan, and Asaiah went to Huldah the prophetess, the wife of Shullam son of Tikvah, the son of Harhas, the supervisor of the wardrobe… She said to them, “Say this to the king of Judah, who sent you to seek an oracle from the Lord: “This is what the Lord God of Israel has said concerning the words you have heard: ‘You displayed a sensitive spirit and humbled yourself before the Lord.

2 Kgs 22:14, 18-19a

A Deuterocanonical Story

I did not include the Deuterocanonical books in my data, but Paidiske pointed a scene to in the book of Tobit (set in the 8th century during the Assyrian captivity) that also passes the Bechdel test.

So she [Edna] went and made the bed in the room as he had told her, and brought Sarah there. She wept for her daughter. Then, wiping away the tears, she said to her, “Take courage, my daughter; the Lord of heaven grant you joy in place of your sorrow. Take courage, my daughter.” Then she went out.

Tobit 7:16 (NRSV)

In this scene, Edna comforts and cares for her daughter Sarah speaking words that pass the Bechdel test. However, in the larger context of the story, Sarah’s tears and Edna’s comfort are connected to men and marriage. Sarah is weeping because she has been engaged to seven men, all of whom were has abducted and killed by a lust demon named Asmodeus on their wedding night. In Tobit 7, her father gives her hand in marriage to an eighth man, but she is worried Asmodeus will kill him as well.

Although this scene passes the Bechdel test, one might point to the story as an example of why these books were considered helpful in some ways, but not rising to the level of inspired holy scripture.

The Savior Arrives

In the gospels, we meet several female characters, many of whom speak to Jesus and some of whom speak to each other. Some passages like Martha telling Mary that Jesus wants to see her (John 11:28) or unnamed women speaking to Jesus (Matt 9:21; 15:22; Luke 11:27; John 4:19-20; 8:11) clearly fail the Bechdel test, but some of the most significant scenes in the story of redemption actually pass the Bechdel test.

In the first passage, Elizabeth and Mary discuss their upcoming pregnancies. Although discussing a male baby is disputable as to whether it truly passes the Bechdel test, one might argue that Jesus does not neatly fit into the hero category. It is fascinating to think that when the second person of the Triune God decided to become a human fetus, his blood cells and DNA, untouched by the stain of sin, were intermixing with Mary’s body and blood. In that moment, we find these words:

When Elizabeth heard Mary’s greeting, the baby leaped in her womb, and Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit. In a loud voice she exclaimed: “Blessed are you among women, and blessed is the child you will bear!”

Luke 1:41ff

Soon after this, baby Jesus is brought to the temple where he meets Simeon and then Anna. After seeing Jesus, Anna is recorded as being one of the first to explain the theology of who this little baby really was. Arguably, this scene partially passes the Bechdel test because a named women is speaking to people (presumably other women) about the redemption of Jerusalem:

There was also a prophet, Anna, the daughter of Penuel, of the tribe of Asher… Coming up to them at that very moment, she gave thanks to God and spoke about the child to all who were looking forward to the redemption of Jerusalem.

Luke 2:36, 38

Moving forward to Jesus’s death, we find a scene in which Mary Magdalene, Mary the mother of James, and Salome discuss the stone being rolled away. The stone is of course related to Jesus, but it is striking that in the most significant event in human history, named women are talking to one another about a major plot point:

Very early on the first day of the week, just after sunrise, they were on their way to the tomb and they asked each other, “Who will roll the stone away from the entrance of the tomb?”

Mark 16:2-3

And finally in a scene that fails the Bechdel test, but is significant because of it, Mary becomes the first to share the good news that Jesus has risen from the dead:

Mary Magdalene went to the disciples with the news: “I have seen the Lord!” And she told them that he had said these things to her.

John 20:18 (cf. Luke 24:10)

It is a wonder that the birth, death, resurrection, and proclamation of Jesus are tied to scenes that pass (or intentionally fail) the Bechdel test.

The Church

As the church spreads through the book of Acts, none of the women in the stories are recorded as directly dialoguing with one another. And yet there are stores of women taking significant roles, such as Lydia lending her home to one of the earliest churches (Acts 16:11-15) and Priscilla and Aquilla team teaching theology courses for Apollo (Acts 18:26). But something that interested me was that, although my dataset was supposed to filter out non-narrative passages, two instances of named women speaking (“greeting”) are found in the end of an epistle to a church and a letter to a pastor:

The churches in the province of Asia send you greetings. Aquila and Priscilla greet you warmly in the Lord, and so does the church that meets at their house.

1 Corinthians 16:19

Greet Priscilla and Aquila and the household of Onesiphorus… Eubulus greets you, and so do Pudens, Linus, Claudia and all the brothers and sisters.

2 Timothy 4:19-21

Claudia is thought to be a British woman living in Rome among those to cared for Paul during his imprisonment. Without dialogue or named characters receiving the greetings, these verses don’t pass the Bechdel test, but they again highlight significant roles played by women in the early church.

One Final Scene

I think there is one more passage worth pointing out that arguably includes two significant female characters. In Paul’s first letter to Timothy, he pens some of the most controversial words about men (1 Tim 2:8) and women (1 Tim 2:9-13) in all of scripture, and then he follows with this:

14For Adam was formed first, then Eve. And Adam was not the one deceived; it was the woman who was deceived and became a sinner. 15But women will be saved through childbearing—if they continue in faith, love and holiness with propriety.

1 Timothy 2:14-15 (NIV)

Although this is how most modern English translations render this passage (ESV is a notable exception), it is important to point out that the plural word “women” in verse 15 is not actually in the Greek, nor is the punctuation between verses. The verb “will be saved” is singular, which means it should be connected to the last person in passage. In addition, the word for “childbearing” is not used anywhere else in the New Testament, and its grammar indicates that it might not be referring to “childbearing” generally, but to a specific childbearing. These grammatical details led some of the church fathers and several modern commentators to render this passage as:

… but she [Eve] will be saved by the [Mary’s] childbearing.

1 Timothy 2:15a (some Fathers, Knight, Guthrie, JFB, Hammond, Peile, Wordsworth, Ellicott)

The point is that although Eve was the first to become a sinner, by God’s grace, the vessel through which deception came into the world will saved by another vessel through which redemption will come. Eve, like all of us, will ultimately be saved by the work of Jesus begun in Mary’s womb. Although most commentators reject this interpretation, I prefer it not only because it avoids all the problems of explaining how childbearing confers salvation, but because it offers one of the most sweepingly beautiful and succinct retellings of the entire Biblical story, of God saving all humanity, male and female from beginning to end, displaying his infinite power and love in the most vulnerable and intimate of ways.

In this final scene of two women together, they are valued not for what they say and not for what they do, but for who they are, for their existence, for being children of God. Whatever the state of our current conflicts over ethnicity, gender, power, and economics, from the first sinner to the last, one day we all will be saved by God the Son becoming a man who was carried by a woman.

Let us then continue in faith, love, and holiness.

Wow. This is really awesome!!! Thanks so much for taking the time to sift through the data and publish it in a usable format. (I found you through Dr. Glahn’s twitter feed in case you’re interested in analytics. I had her as a prof last fall.)

I really wanted to argue Exodus 2 with you because in my head, I remember Moses’s mom telling Miriam to stay and watch. 🙂 But when I looked at the text they don’t interact verbally at all. *sigh* Although, clearly, Miriam had to have told her mom that the Pharoah’s daughter wanted her as a nursemaid. In my book that qualifies even if it happens off-stage. (I love how God uses women and ONLY women to save Moses–and more than once.)

I’m curious why you opted to not include non-narrative portions. Was it to be consistent with Paidiske’s work? I’m thinking Song of Songs 3:5 comes awfully close to passing. Granted, contextually we’re assuming men are the subject of the conversation as it’s speaking of love. But no men are specifically mentioned and it’s discussing self-control. Also, the speaker is named even if the female audience is not.

For that matter, would Song of Songs contain the most female speech percentage-wise of all the books of the Bible? It’s also significant in the greater context of this discussion that the Shulamite is arguably the protagonist (she speaks more than her lover and we see more of her perspective) given the topic. The Bible doesn’t present her as a passive recipient, but an equal partner who pursues her beloved.

Thanks for the great comments! I agree that the non-narrative books are still really interesting to consider, including the women or female personifications in Proverbs, but I hadn’t thought about that particular passage in Song of Solomon. That’s a great addition, even if the audiences isn’t named. Thanks for mentioning that!

Thank you, John, for all the work that went into this post. This is useful information.

I’m wondering if Judith and her unnamed female steward rate a mention (Jud. 8:10; ch. 10; 13:3ff, esp. 13:9-10; cf. 15:12-13; 16:23, etc), especially since Edna and Sarah from the Book of Tobit are mentioned. Though Judith gives her trusted steward instructions, and the pair work together, there is no conversation recorded.

Thanks for mentioning these Marg! Padiske’s post categorizes Judith as a book where named women speak, but only to men. But I think you’re right that the passages you mentioned pass the first Bechdel criteria of having two women together in a scene, even if the dialogue isn’t recorded directly.

As a word nerd employed at an analytics software company, I thoroughly enjoyed this piece! Looking back over my life, I see that every significant turning point in my faith and my part in growing the kingdom of God is marked by a conversation meeting the criteria. So much to think about, here! Praise God for you. I would love to do a similar analysis on the significance of scriptures that align with 1s —1:1, 1:11, 11:1, 11:11, etc. Early this year, I felt called to study all of them in the bible, so I read them all. As I read back over my notes, I don’t need text mining software to see that these scriptures almost always align with key events in God’s persistent goal to bring heaven to earth through people.

That’s really fun that you can combine your work in analytics with the Bible! I, too, have sometimes had fun looking at similarly numbered passages. My favorite is 3:16, especially Leviticus 3:16 compared to John 3:16. But I always try to remember that those verse numbers were added by a printing press owner (Robert Estienne) in the 1550s, so as fun as they are, I don’t put too much weight on their significance 🙂

The Word is living and active! I could see the Holy Spirit using verse numbers from the 1550s to get a message across. 😉